Posted on Sun, Nov. 14, 2004 | ||

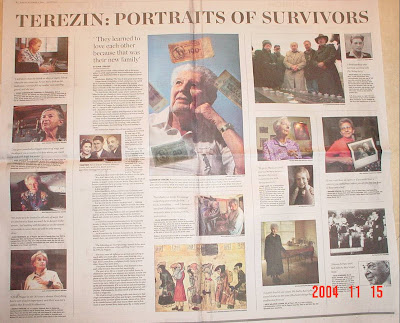

Portraits of Terezin survivors

BY ELINOR J. BRECHER

ebrecher@herald.com

Arno Erban holds a slim volume with a decaying spine, its pink pages graced with handwritten script so elegant and disciplined that it appears computer-generated.

Baudelaire. Kipling. The Czech lyric poet Josef Hora.

Erban doesn't remember which of the boys he cared for at Terezin Home No. 9 transcribed the poems -- there were hundreds -- but he points to the place where Hora's Thanks to the Fire ends in the middle of a line. Right there, says Erban, ``they took the boy to transport.''

To Auschwitz, the death camp, where millions perished in the gas chambers, their remains blasted skyward as fetid smoke through the crematoria chimneys.

Erban was little more than a boy himself when he entered the surreal world of Terezin in January 1942 at 19. Perhaps because he'd been active in the Boy Scouts and YMCA in Prague, he became house master of Home No. 9, a barrack with triple-deck wooden bunks, a table, and a handful of chairs.

For the two years until he was deported to the Auschwitz-Birkenau death complex in Poland, he was a teacher and father figure to boys ages 13-15.

They studied literature and math, played soccer and chess, wrote poems and painted pictures. Erban established a structure based on scouting, with points for good performance in everything from bed making to choir.

He insisted on respect for self and others, and daily good deeds. So when he saw two of his boys carrying a dead body on a stretcher to help out two old men, they got good-deed points for the day.

Home No. 9 didn't house the same 40 boys from beginning to end. Erban, now 82, never knew when the day started if any of his boys would succumb to a ''selection'' -- a euphemism for the death sentence of a transport to ``the east.''

Those selected went to the left; the others to the right.

''We don't know who was luckier,'' he says.

For his birthday in 1943, the boys gave him the book of poems, on paper stolen from the Nazis. They drew the beaver symbol of their scouting ''troop,'' and a dozen or so signed autographed the pages.

A few survived.

After Auschwitz, Erban survived the Geliweicz and Jaworzno camps, death marches, starvation and disease. He stood six feet tall and weighed 75 pounds when he was liberated by the Russian army in January 1945, and couldn't walk for three months.

For his role in the Terezin underground -- making contact with Czech resistance fighters outside the camp -- he became one of 18 civilians awarded the Czech Iron Cross after World War II.

He has three living children and one grandchild. He and his wife, Yolanda, have a bayfront flat in Miami Beach and a home in Caracas, where Erban settled after the war.

A retired accountant and secular Jew, he frequently speaks to Miami-Dade County students on the Holocaust. Given the popularity of body art these days, he chuckles that some kids think the B13126 tattoo on his left arm is ``cool.''

As he watches the Terezin documentary, he smiles at familiar scenes and faces, yet wonders if anyone who wasn't there can understand Hitler's insidious fiction.

* * *

The following are excerpts from a speech Erban gave at a reunion with some of his surviving ''boys'' on June 26, 1994, in Prague:

The boys were all different on arrival and looking so much alike very soon after. Some came from big cities, children of wealthy families; some came from a small village. Some came from a religious family. Some of them didn't know they were Jews.

This place became their home. They learned to love each other because that was their new family . . .

The part of my life as a leader of so-called 'home for children in captivity' now appears as a dream, distant and unrealistic.

I am certain that this was the most important phase of my life, both hard and most constructive. For more than two years, my only thoughts were the boys who were in my care. I tried to give them reason to live in spite of the jail environment. If it were not so sad and hopeless, certainly it would have give me much great personal satisfaction. Unfortunately, the final result of all these efforts ended so tragically. . .

We tried to create something noble and sincere in that tragic environment full of lies and danger, something that despite all the German efforts to make slaves of us, allow us to remain human with clear moral ideals and a firm basis to start normal lives, interrupted by so many years.''

No comments:

Post a Comment